Carbon pricing can be confusing. Simply put, it’s designed to increase costs of burning polluting fossil fuels and encourage cleaner alternatives. It creates a financial incentive for people and businesses to pollute less. Rebates help keep household costs down.

As of 2023, 73 global carbon-pricing instruments were in operation worldwide, covering around 23 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Some are taxes and levies and some are emissions-trading systems. For developing countries starting down the carbon-pricing path, prices can be as low as $1 per tonne of carbon dioxide emissions but reach more than US$125 in countries such as Sweden and Switzerland.

Effective carbon levies rise regularly to give people and businesses time to adjust. Canada’s started in 2019 at C$20 per tonne and went up by $10 a year to $50 in 2022. It’s now increasing by $15 a year until 2030, when it will reach $170 per tonne. The April 1 increase to C$80 (US$59) per tonne adds about three cents to a litre of gasoline — far less than industry-driven price hikes.

A carbon price’s size matters, as it must be high enough to create incentives to use better alternatives to fossil fuels.

To ensure the carbon levy doesn’t create economic hardship for households, especially low- and middle-income, the federal government returns about 90 per cent of the money collected to families through “Canada Carbon Rebate” payments — mailed or deposited four times a year. The remaining 10 per cent is “returned to businesses, farmers and Indigenous groups in the same province or territory where it was collected” to help them reduce emissions.

Rebates are based on family size. Around 80 per cent of households get more back than they spend on the levy. British Columbia and the Northwest Territories have their own plans that meet the federal standard, offering similar rebates or offset payments. (B.C.’s are income-based.) Quebec uses a federally approved cap-and-trade system and reinvests revenues in the fight against climate change.

Rural residents receive an additional 20 per cent rebate.

Evidence from around the world shows carbon pricing works. Environment and Climate Change Canada says 2021 emissions “would have been approximately 18 megatonnes higher in the absence of Canada’s carbon pricing plan.” That’s roughly equal to Manitoba’s annual emissions, CBC notes. The government estimates that “carbon pollution pricing will contribute as much as one-third of Canada’s emissions reductions in 2030.”

Large industrial polluters follow separate pricing systems, which vary by province, that help drive down emissions while keeping companies globally competitive. Consumers pay the price on fossil fuel purchases based on the amount of greenhouse gases created when the fuel is burned. For example, the price on a litre of diesel is higher than on gasoline because diesel produces more CO2.

Although some opponents blame carbon pricing for rising living costs, those are affected to a far greater degree by other factors, especially volatile fossil fuel markets and oil company and other corporate price gouging, as well as supply chain bottlenecks. The impacts of climate-related extreme weather events and pollution — from agriculture and infrastructure damage to health care costs — are also increasingly affecting living costs. Many people rely on carbon rebates to help with these.

A steadily increasing carbon price also offers greater stability and predictability as it sends a clear market signal to businesses and investors and creates incentives for the growing clean energy economy.

Because the wealthiest families pollute far more than middle- and low-income families (larger homes and vehicles, etc.), they end up paying more, while those who pollute less come out ahead because of the rebates.

A peer-reviewed study in Nature found “that if all countries adopt the necessary uniform global carbon tax and then return the revenues to their citizens on an equal per capita basis, it will be possible to meet a 2°C target while also increasing wellbeing, reducing inequality and alleviating poverty.”

Carbon pricing isn’t the only way to combat accelerating climate change, but it’s one of the most useful in a market system. Combined with other tools and solutions, it will help prevent worsening global heating impacts.

Those who argue otherwise seem set on rolling back many necessary climate policies just to derive short-term benefits from fossil fuel consumption. That’s unconscionable.

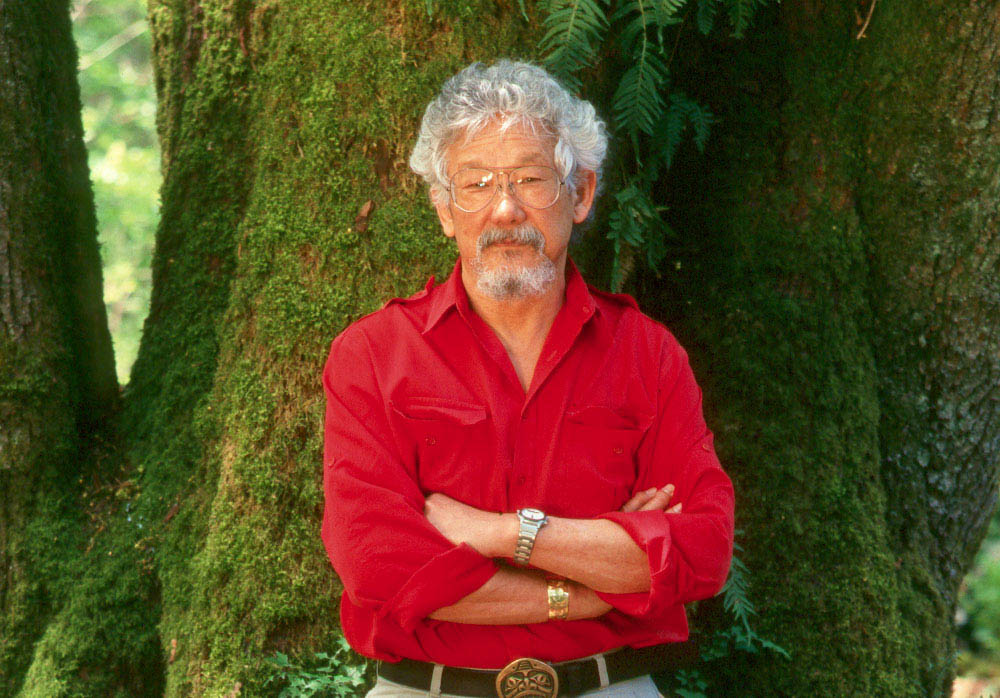

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with David Suzuki Foundation Senior Writer and Editor Ian Hanington.